The Research Project – Part Five

Section five – Increasing the use of mediation amidst FIDIC’s dominance

Blake et al. (2016, pp 24-27) assert that there are circumstances where ADR (and therefore mediation) may be unsuitable but further posits that the court normally sees ADR as potentially useful and cost-effective. Uganda’s mediation rules allow some exceptions, as do the governments in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, etc. And by the same token, not all disputes must be adjudicated. From the survey, 41% of the participants agreed, and 12% strongly agreed that the prevalence of adjudication hindered the use of mediation. Conversely, 10% disagreed, and 3% strongly disagreed. 26% of the participants were undecided, and 9% neither indicated their level of agreement or disagreement. Indeed, Blake et al. (2016, p. 223) posit that construction-related disputes are particularly suitable for mediation. To reverse the bias towards using adjudication for DR requires contract parties in Uganda to amend the DR clause in the GCC of FIDIC’s SFC, plus a look into FIDIC’s Golden Principles (released in 2019).

Tyson (2020) asserts that FIDIC introduced the golden principles to prevent contract parties from heavily amending FIDIC’s GCC, diluting the clauses’ purpose and damaging FIDIC’s reputation. In light of this, FIDIC’s fifth golden principle guides that unless there is a conflict with the law that governs the contract, all formal disputes must be referred to a DAAB/DAB for a provisionally binding decision as a condition precedent to arbitration. With the prevailing mediation law in Uganda and the feedback from the survey, it is sensible to attempt an amendment of the DR clause for FIDIC-based public projects in Uganda to allow the parties to trigger and pursue mediation before adjudication.

Besides, if disputing parties are willing to consider mediation before adjudication, they would probably have already considered and attempted negotiation. This would be killing two birds with one stone. However, as Brooker and Wilkinson (2010, p.197) posit, the DR clause should be redrafted to eliminate doubt about selection procedures, process procedures and mediator appointments. During this drafting process, the question that undoubtedly arises is whether or not mediation should be a condition precedent to adjudication. Making mediation a condition precedent to adjudication would prevent the DR process from being as fluid as it should be – with the ‘black and white’ disputes immediately proceeding to adjudication (if the parties so wish) while the ‘grey’ disputes navigate the mediation path before proceeding to adjudication if unresolved.

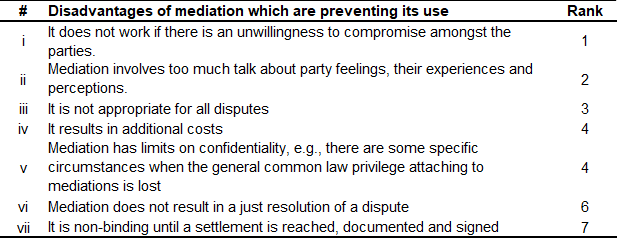

Richbell (2008, pp. 38-40) puts forward some common arguments that disputing parties claim are the reasons for not using mediation to resolve construction disputes. The survey participants ranked these arguments as indicated in Table 3 below.

Table 3: Disadvantages of mediation preventing its use

From the ranking, a party’s willingness to participate and attitude towards the mediation process appears to prevent mediation’s use the most. But perhaps, as Blake et al. (2016, pp 24-27) aver, this is linked to the dispute’s type, value, complexity, and timing. Nonetheless, when the disputing parties know that adjudication is still an option (if mediation fails), they are unlikely to refuse mediation in consideration of its benefits. Indeed, and as Blake et al. argue, the participants ranked the fact that not all disputes can be mediated as third. The fact that mediation led to costs and had limited party confidentiality achieved the same ranking. Finally, and as Richbell highlights, the participants seemed to appreciate that a mediated deal is not necessarily just and understand that once a settlement agreement is signed, it becomes as binding as any contract.

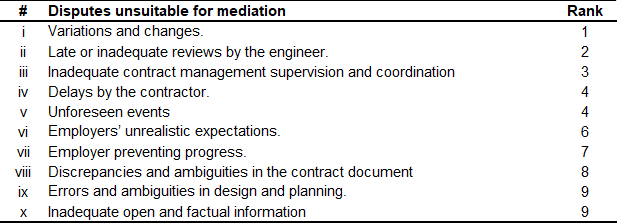

To ascertain the kind of disputes that were most unsuitable for mediation, the survey revealed the ranking in Table 4 below: From this ranking, it is plausible to infer that the dispute category 1-7 is best suited for adjudication while the next three are best suited for mediation, but it is rather impractical to make such a direct inference. In fact, while discussing the research agenda for construction mediation, Ilter et al. (2016) emphasise that further research is required to determine the types of construction disputes most suitable for mediation. This researcher agrees with this.

Table 4: Disputes unsuitable for mediation

When asked to rank why mediation would best resolve construction-related disputes, the participants ranked the preservation of business relationships first, followed by the fact that mediation enables the disputing parties to retain some control over the dispute outcome. Tied in third place was the perception that mediation accords the disputing parties more creativity when settling, and the privacy of the mediation procedure makes it best suited for resolving delicate matters on public infrastructure projects. Tied in fifth place was the fact that mediation enables each party to better understand the other party’s case, narrowing down the issues to achieve settlement more easily and the fact that because mediation is a flexible process that disputants can tailor to meet the needs of a particular dispute.

Responses elicited on the participant’s familiarity with the mediator selection process showed that 6% expressed that they were very familiar, 26% familiar, and 35% somewhat familiar. The remaining 31% were not familiar, while 3% of the participants did not indicate any familiarity level. The study shows that most participants are uncertain about how mediators are selected, which negatively affects their propensity to use mediation. Indeed, Brooker and Wilkinson (2010, p.189) state that a lack of knowledge about mediation processes and practices inhibits interest in construction mediation.

When elucidating the legal framework for mediation in South Africa and Malaysia, Brooker and Wilkinson (p.196) assert that mediation has failed to significantly gain popularity because the construction industry has instead emphasised using adjudication in these jurisdictions and fostered its subsequent development. The Uganda Institution of Professional Engineers (UIPE) actively supports adjudication practice in Uganda, but they do not offer similar support for mediation on construction projects. Yet, 36% of the survey participants strongly agreed that the UIPE must play a significant role in advocating and supporting mediation’s use in construction-related disputes, just as it does for adjudication. In addition, 41% agreed with this. Conversely, 2% disagreed, and 1% strongly disagreed. 11% of the participants were undecided, and 10% neither indicated their level of agreement or disagreement.

Brooker and Wilkinson (pp. 199-200) emphasise that mediation’s use has only flourished when courts and governments deliberately develop enabling policies and strategies to stimulate its use. This is exemplified by GoU’s current policy that makes mediation mandatory (with a few exceptions) for disputing parties before proceeding with litigation as a last resort. Concerning the participants’ familiarity with this policy, 15% expressed that they were very familiar, 27% familiar, and 24% were somewhat familiar. The remaining 33% were not familiar, while 1% of the participants did not indicate any familiarity level. The study showed that most of the participants were uncertain about this policy, yet they were familiar with the potential of mediation to resolve construction-related disputes. Uganda’s mediation policy does not speculate that all construction-related disputes will reach litigation. However, since the Ugandan courts require parties to have considered (and probably attempted) mediation along the DR process of a GoU or MDB-funded project, the policy essentially sends loud signals to the drafters of DR clauses in Uganda’s public infrastructure construction contracts.

Additionally, Brooker and Wilkinson (2010, pp.186-187) claim that many SFC in Malaysia provide for mediation, but there is no evidence of that leading to its high usage, whereas the same government action in Australia and Hong Kong has stimulated the use of mediation. Uganda’s story could thus be successful or not. Is it possible to make this change in Uganda? Of course, change is always met by resistance, but the survey participants’ bias towards mediation is a good indicator that institutionalising this change is worthwhile.

Gerber and Ong (2013, p.139) claim that World Bank shares a close relationship with FIDIC because of the sheer magnitude and the number of construction projects it funds, making it one of the heavier users of FIDIC contracts. They argue that due to this, FIDIC has always consulted closely with the World Bank when revising its SFC. But such amendments commonly originate from FIDIC’s various users, gain momentum, eventually escalate to the various MDBs and finally get the attention of FIDIC’s top brass. The pessimists would argue that the chances of this agenda crystallising in a third-world country like Uganda are slim, but the optimists would say giving it a chance is worthwhile.

Conclusion

The research sought to explore how to increase the use of mediation on construction-related disputes that arise on public sector projects in Uganda, where the contract parties predominantly adopt FIDIC’s SFC. The research outcome is a proposal to introduce deal mediation as a step in FIDC’s DR process before adjudication. It is expected that introducing deal mediation before adjudication will increase the use of mediation, where applicable.

Standing adjudication boards should not cease functionality. Besides, deal mediation somewhat complements the adjudicator’s dispute avoidance role. Though, introducing deal mediation before adjudication essentially implies that the amicable settlement clause in FIDIC’s DR process will be redundant occasionally. Even if many leading authors claim that the use of adjudication is likely to grow, such sentiments should not prevent users in Uganda from tweaking FIDC’s DR process to enable mediation to thrive. Otherwise, if left to its own devices, using mediation will be further curtailed. It is expected that the contract parties will bear an added cost for deal mediation services, but when judged against the overall project cost, the costs associated with deal mediation are normally modest and unlikely to outweigh the benefits of mediation accruing to either party. Deal mediation should apply to public infrastructure projects funded by MDBs and those locally financed by the GoU.

Recommendations

Regarding implementation and enforcement, it is common for people to hold a positive opinion about something and for whatever reason, the same people then act contrary to that opinion. Additionally, Wardle (2020) posits that compared to older FIDIC versions, the density of FIDIC’s new 2017 SFC is a turn off for some practitioners. Possibly, inserting an explicit DR provision for deal mediation will undoubtedly make FIDIC’s new suite of documents a tad bulkier and compound this problem. But perhaps, if the contract parties instead used FIDIC’s latest Green Book (released in 2021 and intended for smaller and lower-risk construction works not exceeding USD 10M), this may cushion that problem. Thus, it is incumbent upon FIDIC practitioners in Uganda to collectively (but tactfully) and via organised movements like UIPE and the Uganda Law Society (ULS) campaign for an appropriate and non-repulsive amendment of FIDIC’s DR process and institute a robust plan to monitor implementation.

From a global perspective, the uniqueness of some projects normally presents perfect platforms to test such proposals on ‘guinea pig’ projects. For instance, Entwistle (2013) claims that a standing board of 12 adjudicators (each nominated by a professional institution) was created to address disputes mushrooming from the major contracts on the London 2012 Olympics project. Entwistle further asserts that the project had an eight-member Independent Dispute Avoidance Panel to assist parties in resolving any matter submitted to them before the adjudicators took over. As a result, dispute avoidance was addressed separately from dispute resolution. He claims that this arrangement was spectacularly successful because only a handful of disputes required the tribunal’s decision.

Similarly, in Qatar (the venue for the 2022 FIFA World Cup), mediation is not yet commonly recognised, but by the same token, to adequately manage disputes on the FIFA World Cup project, the Qatar International Centre for Conciliation and Arbitration and the Qatar International Court and Dispute Resolution Centre developed conciliation rules to encourage constructive dialogue between parties and the use of facilitated settlement of disputes, leading to a formal and binding settlement agreement. Therefore, the proposal to introduce deal mediation before adjudication in FIDIC’s DR process on public infrastructure projects perhaps requires the perfect guinea pig project to test its efficacy.

JOURNALS

Entwistle, M. (2013) Infrastructure Projects: Dispute boards lay strong foundations, The Resolver: The Quarterly Magazine of The Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, Volume 2013, Issue 3 (2013) pp. 10 – 13

Ilter, D, Cakmak, I, P, Ustuner, A, Y, Tas, E. (2016) Toward a research roadmap for construction mediation, International Journal of Law in the Built Environment, Vol. 8 (Issue: 2), pp.176-190

Kakooza, A. C. (2009) Arbitration, Conciliation and Mediation in Uganda: A Focus on the Practical Aspects. Uganda Living Law Journal, Vol. 7 No. 2 December 2009, pp. 268-294.

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS

Uganda Legal Information Institute (2022) The Judicature (Commercial Court Division) (Mediation) Rules, 2007 [Online] Available from: https://old.ulii.org/ug/legislation/statutory-instrument/2007/55 [Accessed 11 April 2022]

BOOKS

Blake S, Browne J. and Sime S (2016) The Jackson ADR Handbook: 2nd ed: Oxford, Oxford University Press

Brooker, P. and Wilkinson S (2010) Evaluation of Construction Mediation. In: Brooker, P and Wilkinson S. eds. Mediation in the Construction Industry: An International Review. New York: Spon Press, p.196

Gerber P. and Ong, B (2013) Best Practice in Construction Disputes: Avoidance, Management and Resolution: 1st ed: New South Wales, LexisNexis Butterworths

Richbell, D. (2008) Mediation of Construction Disputes. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

FIDIC’S GOLDEN PRINCIPLES

International Federation of Consulting Engineers (2019) The FIDIC Golden Principles, 1st ed, Geneva: International Federation of Consulting Engineers FIDIC

WEBSITES

Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy (2021) Qatar’s amazing eight: the stadiums that will host next year’s FIFA World Cup [Online] Available from: https://www.qatar2022.qa/en/news/qatars-amazing-eight-the-stadiums-that-will-host-next-years-fifa-world-cup [Accessed 5 April 2022]

Tyson, V (2020) FIDIC’S Golden Principles – holding back the tide? [Online] Available from: https://www.corbett.co.uk/fidics-golden-principles-holding-back-the-tide/ [Accessed 5 April 2022]

Wardle, N (2020) FIDIC 2017 – two years on [Online] Available from: https://www.bclplaw.com/en-US/insights/fidic-2017-two-years-on.html [Accessed 5 April 2022]

Wardle, N (2022) FIDIC contracts – what’s new for 2022? [Online] Available from: http://constructionblog.practicallaw.com/fidic-contracts-whats-new-for-2022/ [Accessed 5 April 2022]