The Contractor’s Financial Claim – Part Two

In Part One, Arnold narrates the genesis of a contractor’s financial claim amounting to USD 18m, its outright rejection by the Employer and the commencement of a dispute between the contract parties. Arnold, then sets the scene for what turned out to be an interesting revelation of how Dispute Adjudication Boards (DAB) can mitigate disputes on construction projects from spiraling out of control.

Four days after I returned home from Europe, I called Arnold and we resumed our conversation.

Arnold: At the tail end of the summer of 2003, we, (the DAB) received an email captioned Referral of a dispute to the DAB. In the email, the contractor submitted a comprehensive statement of case to us. In accordance with the contract provisions, we had the prerogative to issue a decision to minimise the possibility of the dispute continuing to arbitration. The contract parties and the DAB agreed to convene a hearing towards the end of January 2004 to facilitate the DAB’s decision.

Me: What is a statement of case and where did the hearing take place?

In simple terms, a statement of case is a document in which a party (in this case the Contractor) sets out the particulars of the claim and provides a detailed justification of their financial entitlement.

The contract parties agreed on a venue near the site and the hearing lasted five days. During the hearing, each of the contract parties presented their position on the dispute and these were the key highlights of the hearing, verbatim.

Day One

The Contractor’s submission

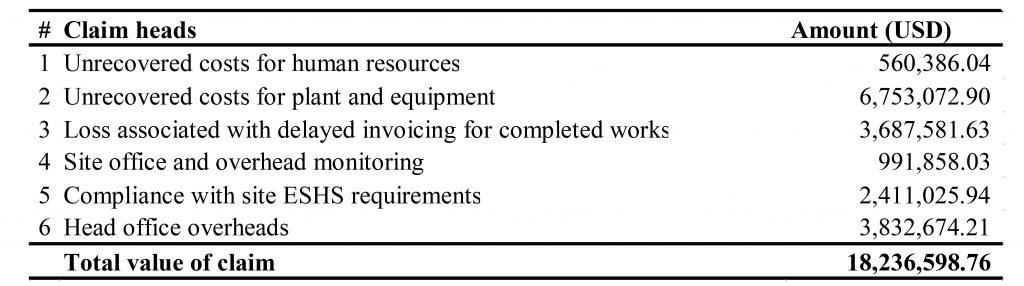

- We consented to a 12-month extension of time with applicable direct costs. However, the claim at hand comprises unrecovered indirect costs for prolongation of the original construction period by 12 months associated with delayed commencement of various sections of work and disruption of our equipment, and human resources as summarised below.

- Our financial claim comprises an analysis of relevant delay events attributed to the Employer. The analysis is supported by various notices to the Engineer (provided as evidence of delay) and it adopts the baseline programme (approved works programme at commencement of the works) to compute the delay.

- Delays prevented us from executing work and receiving timely payment. We seek compensation for the time value of lost income.

- On numerous occasions, we received sites in piecemeal and this lead to unplanned and uncoordinated deployment of our resources. When sites were availed to us, acceleration measures involved increased level of resources and reduced cost efficiency.

The Employer’s submission

- The Contractor’s claim does not consider concurrent delay events.

- The Contractor should comprehensively substantiate their entitlement. As far as we are concerned, there are no contemporary records to prove that the contractor’s plant and equipment was idle. In fact, the contractor’s equipment was either broken down or fully deployed. Without these contemporary records, the contractor cannot substantiate their claim.

- The Contractor has been working in this country for the last 20 years. They are fully conversant with the frequency with which elections are held. Disruption costs associated with political events are not valid because the contractor was aware that elections were eminent and were bound to disrupt his works.

- The Contractor was obliged to undertake the road works with live traffic on site. Challenges and /or delays associated with live traffic are not relevant. Under the contract, adverse unforeseeable conditions are not linked to failure to complete works on time.

- If you extract the portion of the full scope of works that the Contractor was obliged to finish on time and suffered no delay attributed to the Employer, it comprises almost 60% of the entire scope of works. Therefore, seeking to recover prolongation costs for concurrent delays cannot be justified.

- The contractor did not give a notice of intention to slow down the progress of works and cannot at this point seek to take undue advantage of delays he attributes to the Employer.

The DAB’s response to the Employer

In law, exclusion clauses should be interpreted stringently because a party is usually relying on the clause to excuse themselves of breach on their part. In applying such an exclusion, both the interpretation of the clause and the circumstances under which the exclusions comply with the contract, should be undeniably flawless.

In law, exclusion clauses should be interpreted stringently because a party is usually relying on the clause to excuse themselves of breach on their part. In applying such an exclusion, both the interpretation of the clause and the circumstances under which the exclusions comply with the contract, should be undeniably flawless

The situation you are faced with is summarised as follows;

- Construction works commenced in May 2000. By that date, the Employer was already in breach of the contract because the Contractor was not in possession of all the sites. The Contractor could not have foreseen or become aware that the Employers breach of contract at the commencement date would have entitled him to the claim, which you both dispute.

- In the case of continuous delay events (like delayed handover of site resulting from delays in compensation of project-affected persons), a claim notice may be given at any time during the delay period.

- The Contractor’s mobilisation commenced according to the approved programme of works and yet certain packages of the permanent works were not due to commence immediately. Formal notifications of events causing delay and disruption to the Contractor were provided within the notice period required by the contract.

- The Contract required the contractor to undertake geotechnical investigations for the by-pass carriageway to facilitate a design review process to determine the actual route and alignment of the carriageway. Therefore, it was completely within the understanding of the contract parties that the actual carriageway route and alignment would not be finalised at the commencement date and therefore complete access to the site could not be given.

Under these circumstances, providing a notice of delay within 28 days after the commencement date was premature. On this premise, the Contractor has submitted a genuine claim because neither you nor the contractor can pinpoint an exact date when the Contractor should have given an appropriate and timely notice.

Under these circumstances, providing a notice of delay within 28 days after the commencement date was premature. On this premise, the Contractor has submitted a genuine claim because neither you nor the Contractor can pinpoint an exact date when the Contractor should have given an appropriate and timely notice

Me: What was the Employer’s response to the DAB?

Arnold: None

The DAB’s response to the Contractor

- It is difficult to assess the overheads costs on which your claim is based. Could you provide us with back up calculations to prove your overhead calculation?

- Is there an adjustment in your claim for the fact that your deployment of equipment was not as planned?

- How do you arrive at your equipment cost? Does this include depreciation? If it does, this cannot apply if the equipment was idle.

- In your first submission to the Engineer, you sought cost compensation for 15 months. Is this still the case?

- You seek compensation for lost income. However, your costs are not the same if your deployment is not as programmed.

- Can you provide us with audited accounts to prove the costs used in derivation of your financial entitlement?

The Contractor’s response to the DAB

- We seek cost compensation for 12 months.

- We will provide you with audited accounts.

- In our statement of case, we compare the actual costs incurred with the tender costs for each package of work.

- We allocated overheads and a financial weight to each package of work, then, multiplied our overhead rate per day to the weight allocated to each package of work to arrive at our overall financial entitlement.

Me: It appears each of the contract parties presented valid arguments. What was your next course of action?

Arnold: We had to issue a decision in 84 days based on the arguments in the Contractor’s referral, the Employer‘s defence and our knowledge of the project.

On the second day of the hearing, we examined the accuracy of the principles underlying the Contractor’s method of delay analysis and evaluation of additional costs linked to the delay analysis.

On the second day of the hearing, we examined the accuracy of the principles underlying the contractor’s method of delay analysis and evaluation of additional costs linked to the delay analysis

Continue to Part Three

© The Builders’ Garage 2019. Permission to use this article or quotations from it is granted subject to appropriate credit being given to thebuildersgarage.com as the source.