The Research Project – Part Four

Section two – Exposure with (dispute resolution) DR under FIDIC

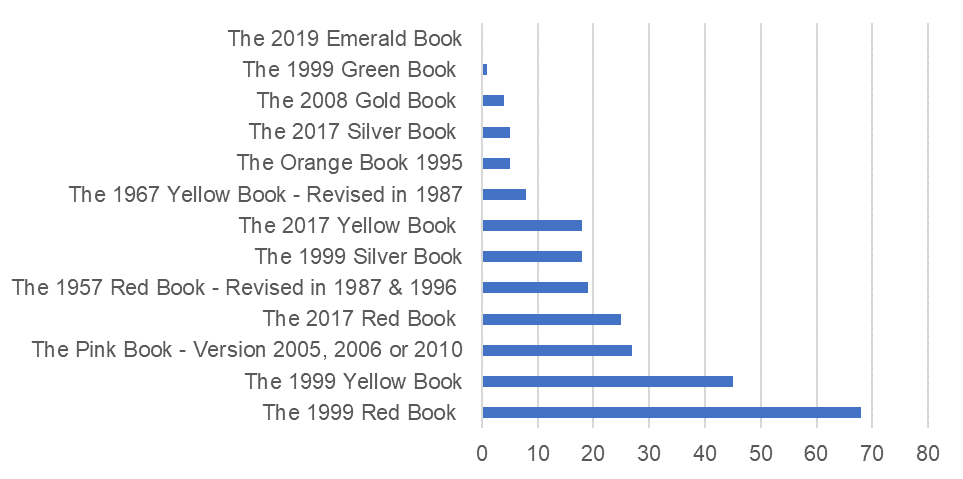

In Figure 7 below, the research shows that the participants predominantly used FIDIC’s 1999 Red and Yellow Books, closely followed by the Pink Book (the MDB Harmonised Edition for bank-financed projects only) and the 2017 Red Book. FIDIC’s first version of the Red Book, the 1999 Silver Book and the new 2017 Yellow Book returned a much lower usage. This is consistent with Charret’s (2015) study, highlighting that the SFCs in FIDIC’s old ‘Rainbow Suite’ are the most widely used international construction contracts in Africa.

Figure 7: The most commonly used FIDIC SFC in Uganda versus the number of projects on which it was used

The survey further revealed that the participant’s rarely used the Orange, Gold, Green, Emerald, and the 2017 Silver Book. Nevertheless, the survey shows that the use of FIDIC’s new Rainbow Suite is gaining momentum. The study also showed that most MDBs are phasing out the Pink Book and embracing FIDIC’s 2017 new suite, where a standing Dispute Avoidance/Adjudication Board (DAAB) is a central premise.

Klee (2018, p. 229-230) highlights that worldwide, FIDIC forms have been used for over 60 years, and they have set an international benchmark that has eased the global construction business. Klee (2018, p. 222) further suggests that the long-term use of SFC like FIDIC in a particular industry sometimes leads to their incorporation into local public procurement legislation. He cites jurisdictions like central and eastern Europe and the Middle East where FIDIC forms are now embedded in public procurement law. The same could arguably be said about Africa (Uganda inclusive) in the future from the above trend.

Dispute occurrence and resolution

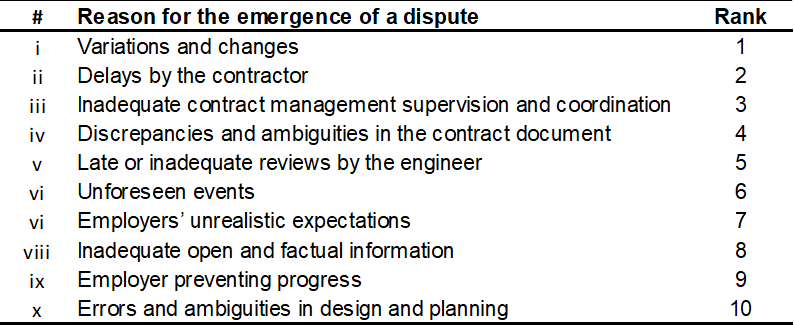

Regarding the occurrence of disputes, 22 participants indicated that no dispute had arisen on the projects they had been involved in. Conversely, 41, 13, 3, and 7 participants indicated that disputes had arisen on up to 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of the projects they had been involved in. Eighteen participants did not respond. Overall, the data reveals that a dispute occurred on most projects where the participants had worked. This is consistent with Richbell’s (2008, pp 1-6) assertion that disputes frequently occur on projects. And when requested to rank the reasons for the emergence of disputes, variations and changes to the original scope of works were the predominant reason, while errors and ambiguities in design and planning were the least cause of disputes (See Table 1 below).

Table 1: Reasons for the emergence of disputes

Besides the list in Table 1, the research revealed a sticky issue related to land acquisition. Some participants indicated that due to Uganda’s ‘unfavourable’ land tenure system – where land belongs to the people, numerous disputes crystallise when the government entities delay, partially hand over a site or completely fail to hand over construction sites on time.

Mante (2014) highlighted that practitioners in Ghana extensively relied on negotiation to resolve disputes due to a lack of regular education and training of professionals in other DR mechanisms. When the survey participants were asked which ADR method is considered the most common, the participants ranked negotiation first and mediation second. Arbitration and expert determination were ranked third and fourth, respectively. Adjudication was ranked as common as conciliation in fifth place, while litigation and mini-trial came in at seventh and eighth, respectively. This implies that even though both the MDB and GoU financed SFC accord adjudication the first priority for DR, the contract parties are perhaps finding a way to circumvent adjudication and amicably resolve their disputes via negotiation and mediation. Or they may be ignorant about the feasibility of other ADR methods, as Mante (2014) posits.

Section three – Amicable settlement

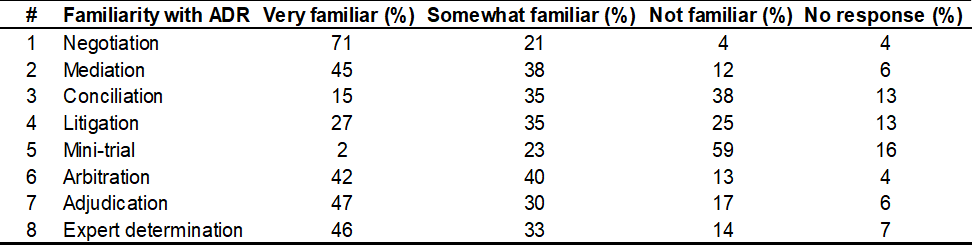

Concerning ADR familiarity, the research revealed that 71% of the participants were very familiar with negotiation, distantly followed by adjudication, expert determination, mediation and arbitration at 47%, 46%, 45% and 42%, respectively. Mini-trial, conciliation and litigation were the most unfamiliar, with 59%, 38% and 25%, respectively (See feedback in Table 2 below).

Table 2: Participant’s familiarity with ADR

Regarding the familiarity with FIDIC’s amicable settlement clause, 85% of the participant’s expressed familiarity with FIDIC’s amicable settlement clause, i.e., 19% were very familiar, 45% familiar, and 21% were somewhat familiar. The remaining 13% were unfamiliar, while 2% of the participants did not indicate any familiarity level. On assessing whether the participants had ever participated in an amicable settlement, the survey revealed that 34% had not participated. In comparison, 49% had participated in an amicable settlement on only a few occasions. Conversely, 5% indicated that they participated very often, while 10% stated that they had participated often. 3% of the participants did not indicate their level of participation. Overall, the research revealed a high level of familiarity with amicable settlement but a correspondingly significantly lower level of involvement. This perhaps implies that either the disputes were resolved in the first instance via adjudication (with participation from project managers, engineers and consultants) or amicable settlement went ahead but with a different (and possibly higher) calibre of stakeholders – probably in the frame of directors and or legal representatives from either contracting party. Besides, this is perhaps why Richbell (2008, p.57) cautions that sometimes the parties who come to mediation have little or no authority and may decide nothing and take no responsibility.

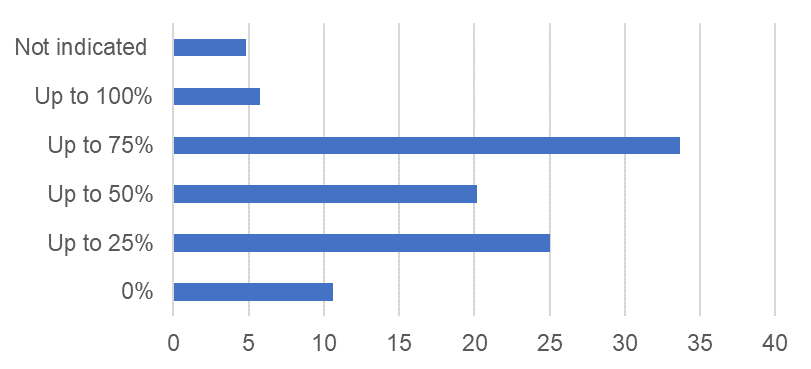

As observed in Figure 8, when requested to rank which ADR method the survey participants considered the most commonly adopted by contract parties during amicable settlement, negotiation came first and mediation second, followed by conciliation and expert determination. Indeed, data from construction studies in Australia show that mediation is the most frequently deployed DR method after negotiation (Brooker and Wilkinson, 2010, p.190). Regarding the percentage of disputes that were resolved at amicable settlement, 34% of the participants stated that up to 75% of disputes were solved by amicable settlement, while 25%, 20% and 6% of the participants stated that up to 25%, 50% and 100% respectively, of the disputes, were resolved by amicable settlement. Thus, amicable settlement was observed to have a considerable potential to resolve most of the disputes occurring on public projects in Uganda.

Figure 8: Percentage of disputes that were resolved at amicable settlement versus the percentage proportion of the survey participants

In this regard, Charret (2015) claims that during amicable settlement, the contract parties benefit from a reasoned decision that provides an independent view of the legal merits of each party’s position and that this should be a useful starting point for any commercial negotiations thereafter. Indeed, one of the survey participants, a lawyer with 35-40 years of experience on public projects and working as an independent neutral arbitrator and adjudicator, indicated the following:

‘Mediation is suitable for all disputes and can be a great way of resolving disputes. This is because strictly ‘contractual’ solutions are often not the best. However, the problem with mediation is that most public employers cannot act on settlements. Dispute Boards allow the parties to move forward because they must follow the decision. It seems that settlements are more acceptable if they come after a Dispute Board (DB) decision.’

However, amending a DB’s decision at amicable settlement is not straightforward. For instance, assuming a Ugandan government ministry or parastatal triggered amicable settlement to mediate an adjudicator’s decision, hoping to reduce a contractor’s award from USD 2.5M (awarded as cost compensation for an employer risk event) to USD 1.5M. Is the employer likely to succeed? Your guess is as good as mine. Or if, instead, the contractor triggered amicable settlement in the hope of securing more time (possibly with related costs) to complete works after a DB had only awarded half the time that the contractor had initially requested without corresponding prolongation costs for the time extension. Is the employer likely to agree? Possibly not.

Besides, any such agreement on a public project in Uganda must be approved by a separate committee, different from the project implementation unit, before enforcement under the contract. Richbell (2008, p.57) reiterates this and argues that public bodies and government departments usually have to get a negotiated settlement ratified by a committee. In Uganda, this committee is referred to as a Contracts Committee (CC). The CC operates within strict boundaries and in the taxpayer’s interest. Therefore, if settlements of this kind are impractical and unlikely to be approved by an entity’s CC (if at all amicable settlement succeeds), Charret’s view is somewhat diluted because the amicable settlement clause will occasionally be redundant for certain disputes. In addition, the CC tends to operate oblivious of the time bars in FIDIC’s SFC, yet the DB’s decision becomes binding if the amicable settlement window elapses without the CC’s approval. Yet, prior mediation before adjudication could have altered the course of things. But this does not mean that FIDIC’s time bars are inapplicable before a dispute goes to adjudication.

Section four – Breaking the barriers to mediation’s use

The survey participants were asked to what extent they agree with adjudication being accorded the priority for dispute resolution in FIDIC’s SFC. The survey revealed that 42% of the participants disagreed with this status quo, and 13% strongly disagreed. Conversely, 10% strongly agreed, while 20% agreed with FIDIC’s status quo. 11% of the participants were undecided. 4% of the participants neither indicated their level of agreement nor disagreement with this status quo. Furthermore, 44% of the participants agreed that mediation was better than adjudication for resolving construction-related disputes. 22% strongly agreed, while 22% were undecided. 9% disagreed, and 2% strongly disagreed. Only 1% of the participants neither indicated their level of agreement nor disagreement. In addition, 40% of the participants strongly agreed that contract parties should attempt mediation before adjudication, while 42% agreed. 5% were undecided, 7% disagreed, and 1% strongly disagreed. Only 1% of the participants neither indicated their level of agreement nor disagreement. Related to this, 48% of the participants were familiar with mediation and its advantages and disadvantages, 14% were very familiar, 28% were somewhat familiar, and 10% were unfamiliar. We are thus left pondering what can be done to expressly incorporate this overwhelming preference for mediation into FIDIC’s SFC during the implementation of public projects in Uganda, at what point in the DR process and for what kind of dispute.

While deliberating dispute avoidance in the construction industry, Richbell (2008, p.119) posits that involving a neutral party when disagreements are unresolved can foster settlement. Richbell (2008, pp. 123-127) discusses deal and project mediation and asserts that the former is adopted when an independent third party is introduced into a negotiation process to help the negotiating parties achieve the best outcome, while the latter positions the mediation process into construction projects right from the start, focussing more on dispute avoidance (creating an atmosphere of cooperation and partnering) than on resolution – via a mediation pairing appointed from the beginning. Gidwani (2007) asserts that a single mediator can also conduct project mediation.

While discussing DB alternatives, Gidwani (2007) opines that project mediation is best used as a supplement to FIDIC’s DR structure, but preferably with an ad hoc board and cautions that where the contract parties already plan on constituting a standing board, an overly of project mediation will most likely be revolting. Therefore, a standing board should be maintained so that the parties have recourse to a formal tribunal if they cannot resolve their differences. Besides, Gidwani argues that project mediation appears cheaper than a standing board from a cost perspective. Consequently, we can infer that deal mediation would be cheaper than project mediation. However, on further scrutinising FIDC’s new SFC, standing boards will be with us for the foreseeable future, essentially compelling contract parties to consider deal mediation. Besides, Shapiro (2003, cited in Richbell 2008, p.125) claims that deal mediators often venture where parties cannot and where mediators in ordinary DR dare not.

Richbell (2008, p.123) suggests that mediation is applicable at the beginning, middle, and end of a construction project but claims mediation rarely happens. Additionally, Agapiou and Clark’s (2013) study of Scottish construction clients’ interaction with mediation yielded an opinion that mediation is best suited to ‘grey’ issues, where there may be uncertainty, instead of ‘black and white’ issues, where adjudication would be considered more appropriate because there isn’t vast room for compromise. Bunni (2005, p.440) also claims that amicable DR methods are successful when the parties believe that the disputes in question are not ‘black and white’. Perhaps having a deal mediator on a construction project would foster mediation for ‘qualifying disputes’ at an early stage and prevent adjudicators from navigating the challenges that arise when adjudicators entangle themselves in a quasi-mediator role.

Indeed, Charret (2015) claims that where a standing board is in force, its members are uniquely positioned to assist the contract parties to avoid disputes. He asserts that when operating in dispute avoidance mode, the DB essentially employs mediation skills to facilitate DR. Entwistle (2013) also claims that DBs can contribute to both dispute avoidance and DR. However, Pickavance (2016, p.376) cites Lloyd J’s ruling in Glencot Development & Design Co v Ben Barrett & Son Contractors[1] as an indicator that even if the contract parties have consented to their adjudicator acting as a mediator, the adjudicator risks being perceived as biased if the adjudicator eventually adjudicates a dispute that they had unsuccessfully attempted to mediate. Thus, if the parties engaged a deal mediator, impartiality on the adjudicator’s part would be ruled out, and the adjudicator would undoubtedly be privy to the outcome of the deal mediation (unless the contract parties wish otherwise) but not the private and confidential discussions that resulted from the mediation. The adjudicators would probably be left to deal only with ‘black and white’ disputes or those where mediation failed. This unlocks the opportunity to introduce deal mediation in FIDIC’s SFC before either party refers a dispute to adjudication.

Continue to Part Five

CASE LAW

[1] Glencot Development and Design Co Ltd v Ben Barrett & Son (Contractors) Limited [2001] 2 WLUK 352, 2001 WL 239771 at [23]-[25]

JOURNALS

Entwistle, M. (2013) Infrastructure Projects: Dispute boards lay strong foundations, The Resolver: The Quarterly Magazine of The Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, Volume 2013, Issue 3 (2013) pp. 10 – 13

Gidwani, K. (2007), Alternatives to the dispute Board-Project mediation 5 October 2007, The FIDIC Contracts Conference 2007.

THESIS

Mante, J. (2014) Resolution of construction disputes arising from major infrastructure projects in developing countries – A case study of Ghana [Doctor of Philosophy Thesis]. University of Wolverhampton

BOOKS

Brooker, P. and Wilkinson S (2010) Evaluation of Construction Mediation. In: Brooker, P and Wilkinson S. eds. Mediation in the Construction Industry: An International Review. New York: Spon Press, p.196

Bunni, N. G. (2005) The FIDIC Forms of Contract. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Klee, L. (2018) International Construction Contract Law. 2nd ed. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons

Pickavance, J (2016) A Practical Guide to Construction Adjudication. 1st ed. Oxford: Willey Blackwell

Richbell, D. (2008) Mediation of Construction Disputes. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Limited.