The Research Project – Part Three

Abstract

Most public infrastructure contracts in Uganda are based on the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) standard forms of contract (SFC), which accord adjudication the first priority for dispute resolution. This essentially curtails the use of other alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods. This research explored what could be done to increase the use of mediation on construction-related disputes that arise on public projects in Uganda, where the contract parties predominantly adopt FIDIC’s SFC.

A qualitative survey conducted on 104 private and public sector professionals in Uganda revealed that the Government of Uganda (GoU) and consultancy firms employ most FIDIC practitioners and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) finance most public projects in Uganda. The GoU also funded numerous public projects locally. The survey further indicated that the predominant use of FIDIC’s SFC inhibits practitioners from using mediation but revealed an overwhelming preference for using mediation (instead of adjudication) to resolve construction-related disputes. Additionally, the study unearthed the practitioners’ familiarity with amicable settlement but exposed their limited involvement in amicable settlement. The study also revealed that most of Uganda’s FIDIC practitioners were unaware of the mediator selection processes and the prevailing mediation law in Uganda.

As a remedy, the study proposed introducing deal mediation as a step in FIDC’s DR process before adjudication while maintaining the use of FIDIC’s standing boards. However, achieving this requires a collective, tactful and organised government institutional campaign for an appropriate amendment of FIDIC’s DR process plus a robust implementation plan for MDB and GoU, financed public projects. Uganda’s leading educational institutions must also re-think the current approaches to practitioner training in ADR and craft relevant and practical training to improve practitioner competency in ADR. And on a global scale, testing deal mediation on public projects may necessitate a ‘guinea pig’ project to test its efficacy.

Methodology

This paper answers the research question that emerged from the literature review. Considering the literature reviewed during the initial stages of research, the researcher adopted a contractual and sociological theoretical perspective to answer the research question. Besides, Ilter et al. (2016) suggested that the research in construction mediation should explore mediation in public projects.

Naoum (2019, p.5) suggests that research design encompasses deciding on the type of data to be collected, and this can either be qualitative or quantitative. Fellows and Liu (2015, p.9) assert that qualitative research is exploratory and empirical, and the data are non-numerical. Fellows and Liu also emphasise that qualitative research best suits scenarios where a researcher interprets a phenomenon’s significance. Yin (2016, p.6) claims that qualitative research enables a researcher to conduct in-depth studies about various topics. Qualitative research focuses on exploring illuminating instances in as much detail as possible and aims to achieve depth rather than breadth (Blaxter et al., 2010, p.65). Therefore, the researcher adopted a qualitative approach.

As Naoum (2019, pp.70-73) guides, the researcher developed a questionnaire to collect first-hand raw data and circulated the questionnaire by email (as suggested by Blaxter et al., (2010, p.186) to specific public infrastructure professionals in Uganda. This prevented skewed results and increased the probability of response. The researcher discarded interviews because McNeil and Chapman (2005, p.59) aver that interviews can cause bias in respondents’ answers. Moreover, questionnaires allowed for anonymity, which interviews could not provide. The respondents completed the questionnaire anonymously, and the internet equally returned anonymous feedback.

To methodically answer the research question, this paper has five sections. Section one analyses the survey participants’ professional background and experience on public infrastructure projects and clarifies who finances public projects in Uganda. Section two studies the extent of use of FIDIC’s various SFC in Uganda, the frequency of dispute occurrence, what causes disputes on public projects in Uganda and the most common DR method known to the survey participants. In section three, the paper examines the participant’s understanding and experience with amicable settlement under FIDIC and their familiarity with other ADR methods besides mediation. Section four investigates the barriers to using mediation under FIDIC contracts and the participant’s perception of using mediation instead of adjudication for DR. Section five analyses the extent to which the prevalence of adjudication hinders mediation’s use and whether Uganda’s FIDIC practitioners are aware of the prevailing mediation law in Uganda, let alone how mediators are selected and what the pros and cons of using mediation are. The paper ends with conclusions and recommendations derived from rational and coherent arguments in the preceding sections and makes some recommendations for further research.

Argument and Evidence

Section one – Professional background and specific work experience

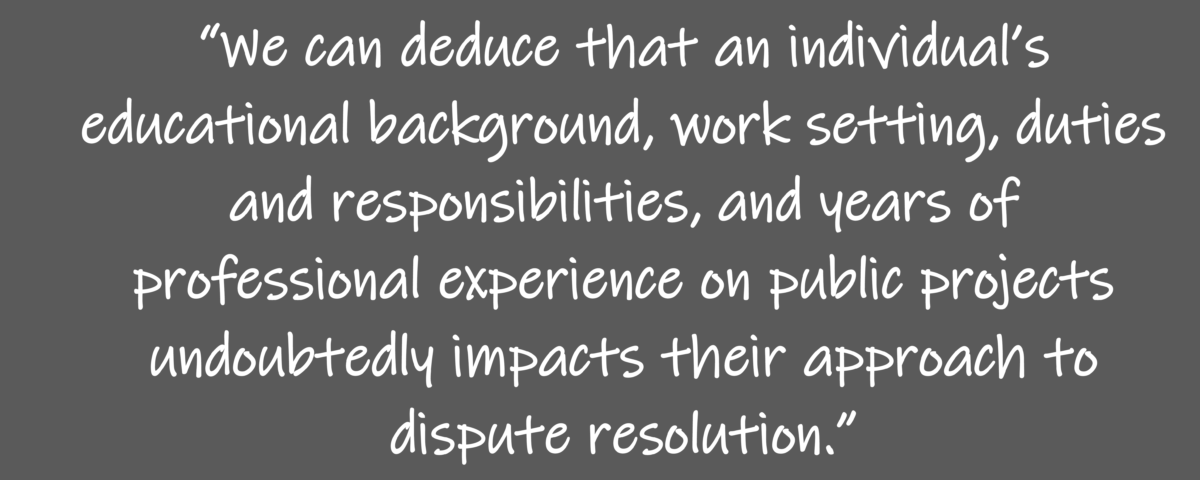

The feedback revealed that 71% of the participants had a civil engineering background, 13% a construction management background and 4% a legal background. Environmental engineers, quantity surveyors and mechanical engineers each comprised 3%. The participants also included an architect and an auditor, each representing a 1% proportion. Only 1% did not indicate their professional background (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Participant’s educational background versus the percentage proportion of the survey participants

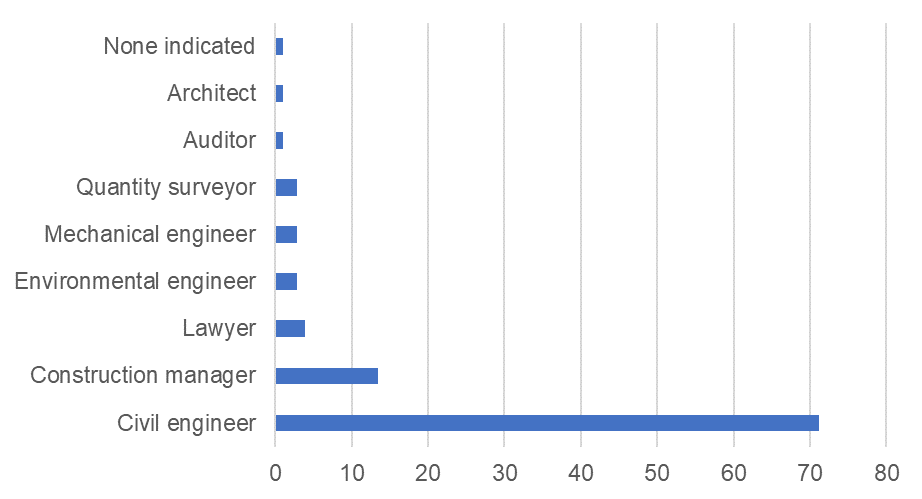

Furthermore, consultancy firms employed 34% of the participants, government parastatals employed 27% and construction companies employed 13% of the participants. 9% worked with government ministries, 5% were independent ADR specialists, 4% worked with MDBs, and 3% were freelance consultants. Retired professionals and those currently engaged in private business each contributed a 2% proportion, while law firms and non-government organisations each employed a 1% proportion. Only 1% did not indicate their employment status (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Participant’s employment status versus the percentage proportion of the survey participants

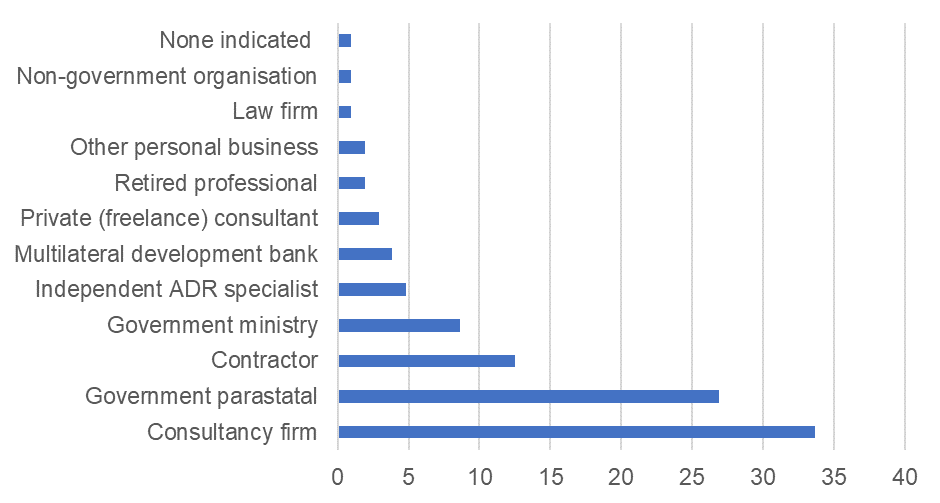

84% of the participants had between 0 and 25 years of experience on public infrastructure projects, with the largest proportion having 10-15 years of experience. The remaining 15% of the participants had experience in public infrastructure projects exceeding 25 years. Only 1% of the participants lacked experience in public infrastructure projects, and another 1% did not state their level of such experience (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Participant’s years of experience on public infrastructure projects versus the percentage proportion of the survey participants

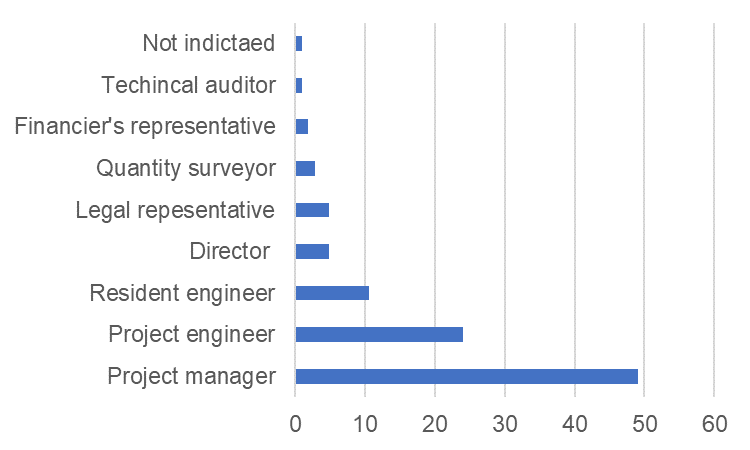

Responses solicited on the specific role played by each participant on the projects indicated that 49% of the participants had worked or were working as project managers, 24% as project engineers and 11% as resident engineers. The rest worked as directors (5%), legal representatives (5%), quantity surveyors (3%), funders representatives (2%), and technical auditors (1%). Approximately 1% did not indicate their role (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: Participant’s roles in the project versus the percentage proportion of the survey participants

Richbell (2008, p.30) argues that individuals perceive the same events and facts differently, and because of this, they are expected to have varying opinions about things. Richbell further suggests that mediation, unlike most other DR methods, considers this uniqueness of individuals. Hence, we can deduce that an individual’s educational background, work setting, duties and responsibilities, and years of professional experience on public projects undoubtedly impacts their approach to DR. Therefore, since the survey participants had varying educational backgrounds and years of experience, worked in different organisations and had taken on varying roles on various public projects, their propensity to use mediation, let alone know or appreciate mediation’s merits or demerits as an alternative to adjudication (or any other DR method) will vary.

The survey revealed that project managers and engineers interacted most with public projects. Yet, Agapiou (2015) highlights that such professionals are less likely to have undergone formal ADR education or practised it. Kakooza (2009) suggests a shift in ADR training in Uganda. But this training appears to be packaged solely for lawyers and not purposefully crafted for project managers and engineers. Thus, depending on how disputes mushroom and the competence of these professionals to resolve the disputes adequately, things can go out of hand. Project managers and engineers require sufficient DR knowledge throughout a project’s lifecycle. This they can acquire through formal schooling, training via bespoke continuous professional development (CPD) programmes or from the school of hard knocks. Indeed, while undertaking research on the mediation centre in Kwara State, Nigeria, Barakat et al. (2020) revealed an urgent need for training and reskilling lawyers, judges, and other vital stakeholders handling construction-related disputes.

Concerning practitioner training and education, Kathrani (2020) posits that technology is changing how training is delivered. She further asserts that if training is not innovative and exciting and lacks appropriate content and substance, it may not achieve its objective. The school of hard knocks reveals that practising professions in Uganda and worldwide always claim to be busy. Yet, they simultaneously crave practical and well-packaged knowledge that improves their competence.

Since project managers and engineers do not work in isolation, there is a need for Uganda’s public infrastructure practitioners, both in government and the private sector, to devise and enforce practical measures to sustainably support and nurture all the professionals requiring DR knowledge. The Uganda Institution of Professional Engineers (UIPE), Uganda Law Society (ULS) and perhaps the leading higher educational institutions in Uganda need to re-think their approach to ADR training to make it more relevant and effective.

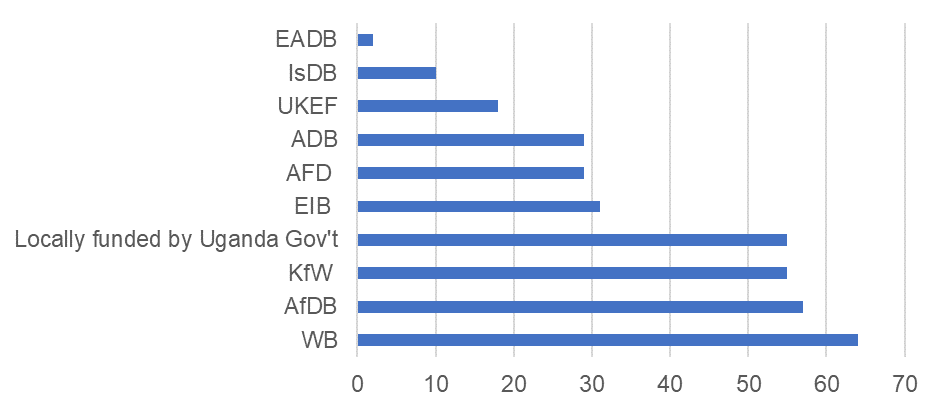

Project financing by MDBs and GoU

Furthermore, the survey revealed that besides involvement in projects locally financed by the GoU, most survey participants had worked with more than a single MDB. In some cases, multiple MDBs funded the same projects. The research also revealed that the World Bank (WB), African Development Bank (AfDB), KfW Development Bank, European Investment Bank (EIB), Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the French Development Agency (AFD) are the key financiers of public projects in Uganda. The Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) and United Kingdom Export Finance (UKEF) also featured but with a much lower frequency (See Figure 5).

Figure 5: Project financiers versus the number of projects that they financed

This trend confirms Gerber and Ong’s (2013, p.139) assertion that the World Bank is indeed the largest financier of public projects. It also reinforces Gerber and Ong (2013, pp.142-145) and Chapman’s (2009) suggestion that adjudication will undoubtedly grow in popularity and frequency because the World Bank and other MDBs support and encourage their borrowers to use FIDC’s SFC. Gerber and Ong (2013, p.137) further argue that because earlier Dispute Resolution Boards (DRBs) successfully fostered dispute avoidance, FIDIC was motivated to develop Dispute Adjudication Boards (DABs).

However, Gerber and Ong further highlight the existence of research suggesting a disappointingly negative impression of DABs within the construction sector, suggesting that many FIDIC users tend to delete the adjudication provision, or if the MDBs oblige them to retain it, they disregard it after contract signature and deliberately fail to appoint DAB members. They assert that some contract parties wait 6–12 months after works commenced, or even long after a dispute has arisen, before establishing the DAB – a familiar situation in some Ugandan public contracts. Thus, even with the low uptake of mediation on public projects in Uganda, the feature of adjudication in Uganda’s construction sector is also threatened – a conundrum that may warrant further research.

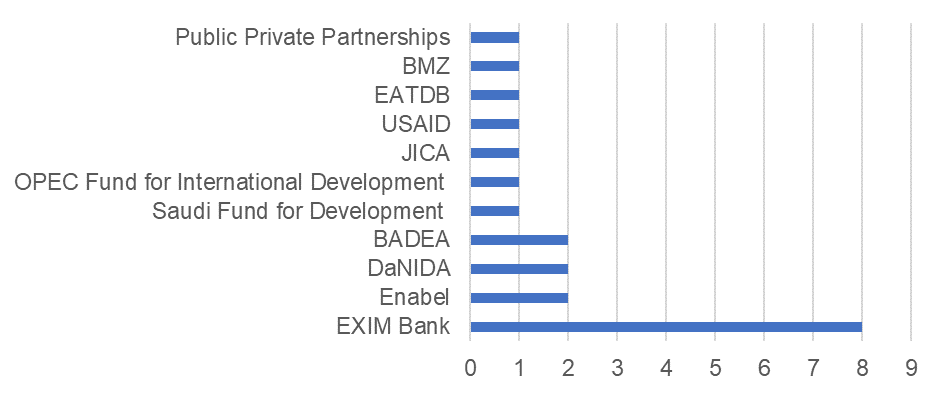

The research further revealed a category of funders from Asia, i.e. The Export-Import (EXIM) Bank of China, the far east, i.e., Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the middle east, i.e., Saudi Fund for Development (SFD), OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID), Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA), Scandinavia, i.e., Enabel – The Belgian Development Agency, Danish International Development Agency (DaNIDA), the west, i.e. the United States of America (USA), i.e., United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and in Europe (Germany) – The Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The research also revealed the East African Community financiers, i.e., the East African Trade and Development (PTA) Bank and Public-Private Partnerships (See Figure 6).

Figure 6: Second category of project financiers versus the number of projects they financed

However, compared to the key project financiers, this category had a distinctly limited frequency, e.g., the EXIM Bank featured only eight times, Enabel, DaNIDA and BADEA each featured twice, while the rest only featured once. The trend established with the EXIM Bank prompted further investigation into China’s use of FIDIC. The investigation revealed that five FIDIC SFC, i.e., the Red, Yellow, Silver (1999 and 2017) editions, Gold and White books, are now available in the Chinese language. Therefore, it is only a matter of time for China’s EXIM Bank to become a major financier of public infrastructure projects and a promoter of FIDIC’s SFC.

The Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority (PPDA) regulates all public procurements in Uganda. The fact that several participants indicated that they had worked on projects financed by the GoU prompted a deep dive into two SFC for public works. Consequently, a review of PPDA’s standard bidding document (SBD) for works under open and restricted bidding (issued September 2019), used by Uganda’s central government, and the SBD used by Uganda’s local government (issued September 2020), revealed that the only DR options in the General Conditions of Contract (GCC) are adjudication and arbitration. The option to use mediation is non-existent in the GCC of either SBD. At the bidding stage, the GCC are embedded in the SBD and become part of the construction contract at the end of the bidding and pre-contract negotiation process.

On further scrutiny, clause 33.1 of the GCC in both SBD states that if a contractor believes that a decision taken by the project manager was either outside the authority given to the project manager by the contract or that the decision was wrongly taken, the decision shall be referred to any adjudicator appointed under the contract within 14 days of the notification of the project manager’s decision. Clause 34.3 further states that either party may refer an adjudicator’s decision to an arbitrator within 28 days of the adjudicator’s written decision. The option to pursue amicable settlement before arbitration (like under FIDIC) is non-existent in the local SBD. Nevertheless, the contract parties retain some flexibility (just like under FIDIC) to amend the Special Conditions of Contract (SCC) in these SBD so that the DR provisions in the SCC eventually prevail over those in the GCC. This investigation showed that FIDIC’s DR process has more flexibility than the DR process in Uganda’s SFC for similar works.

Though, since government and parastatal employees constituted 36% of the survey participants, the likelihood of the PPDA amending the GCC (in the SBD) to include mediation as a prior DR option for GoU-financed projects is likely to be hindered by the well-known red tape that exists in most third world government institutions, Uganda inclusive. Thus, due to an observed bias towards adjudication and arbitration, it is likely to be a challenge (at least in the foreseeable future) for contract parties to prioritise using mediation before adjudication in the DR process.

Continue to Part Four

JOURNALS

Agapiou, A. (2015) The factors influencing mediation referral practices and barriers to its adoption: A survey of construction lawyers in England and Wales, International Journal of Law in the Built Environment, Volume 7 (No. 3), pp. 231-247.

Barakat A. R, Shittu A. R and Idris A. T (2020) Role of Mediation in Resolving Construction Disputes: A Study of Mediation Centre in Kwara State, Islamic University Multidisciplinary Journal, Volume. 7 (2), 2020, pp. 80-88

Chapman, H, J, P (2009) Dispute boards on major infrastructure projects, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Management, Procurement and Law 162, Issue MP1, February 2009, pp. 7-16

Ilter, D, Cakmak, I, P, Ustuner, A, Y, Tas, E. (2016) Toward a research roadmap for construction mediation, International Journal of Law in the Built Environment, Vol. 8 (Issue: 2), pp.176-190

Kakooza, A. C. (2009) Arbitration, Conciliation and Mediation in Uganda: A Focus on the Practical Aspects. Uganda Living Law Journal, Vol. 7 No. 2 December 2009, pp. 268-294.

Kathrani, P (2020) Towards a new model of technical education, The Resolver: The Quarterly Magazine of The Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, Volume 2020, Issue 3 (2020) pp. 28 – 29

BOOKS

Blaxter, L, Hughes C. and Tight, M. (2010) How to Research. 4th ed. Glasgow: McGraw Hill Education

Fellows, R. and Liu, A. (2015) Research Methods for Construction. 4th ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell

Gerber P. and Ong, B (2013) Best Practice in Construction Disputes: Avoidance, Management and Resolution: 1st ed: New South Wales, LexisNexis Butterworths

McNeil, P. and Chapman, S. (2005) Research Methods. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge

Naoum, S.G. (2019) Dissertation Research and Writing for Built Environment Students. 4th ed. New York: Routledge

Richbell, D. (2008) Mediation of Construction Disputes. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

Yin, R. K. (2016) Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press

WEBSITES

International Federation of Consulting Engineers (2019) FIDIC signs ground-breaking collaboration agreement with China International Contractors Association [Online] Available from: https://fidic.org/node/23602 [Accessed 5 April 2022]

International Federation of Consulting Engineers (2020) FIDIC signs major translation and publication agreement with leading Chinese multimedia and publishing group [Online] Available from: https://fidic.org/node/27502 [Accessed 5 April 2022]

International Federation of Consulting Engineers (2020) Which FIDIC Contract should I use [Online] Available from: https://fidic.org/node/149 [Accessed 11 April 2022]

Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority (2022) Standard Bidding Documents for the Central Government for Works under Open or Restricted Bidding [Online] Available from: https://www.ppda.go.ug/download-reports/legal/standard-bidding-documents/ [Accessed 5 April 2022]

Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority (2022) Standard Bidding Documents for the Central Government for Works under Open or Restricted Bidding [Online] Available from: https://www.ppda.go.ug/download-reports/legal/standard-bidding-documents/ [Accessed 5 April 2022]